indeed

v1.1.0

Published

Boolean helpers for node.js

Downloads

205

Readme

Indeed

Boolean helpers for node.js

Why Bother?

Simple booleans are efficient and not that hard to use in javascript, so what's the value of a DDL for booleans? Mainly, I just find booleans one of those things that, if I think too hard about them, then I get lost. The project was born when I had

if (!oneThing && anotherThing) {

// . . .

}but then realized I actually needed the negative of anotherThing. So I changed it to

if (!oneThing && !anotherThing) {

// . . .

}at which point, I started wondering if that was the same as

if (!(oneThing && anotherThing)) {

// . . .

}And then I thought, what I really want is to say

if (neither(oneThing).nor(anotherThing)) {

// do something

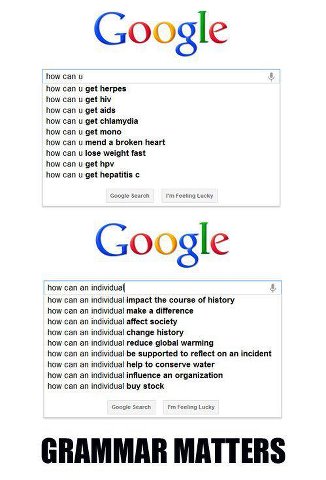

}and thus the module "neither" was born. And then I later changed it to "indeed", which was more globally usable as a boolean helper. A bit of an anti-climatic ending, really. At any rate, this library is just a set of boolean helpers to put if statements into English-like syntax. Note that I used to be an English teacher and thus, that syntax is extremely opinionated and grammatically correct. Grammar is your friend.

Ahem . . . now on with the API.

Installation

npm install indeed --savethen

var helpers = require('indeed');or

// Set up global methods.

// Mainly useful because I don't like having to say "if (helpers.indeed(a)..."

require('indeed')();Usage

When you require('indeed'), you'll get an object with methods that begin boolean chains: indeed, either, neither, both, allOf, oneOf, noneOf, anyOf, nOf, and expect. These function are roughly the same - they allow you to assess conditions using natural language. These conditions are processed first in first out, so they can behave slightly differently than normal boolean logic. For example: if (a && b || c) becomes if (indeed(a).and(b).or(c)) as you might expect. However, if (indeed(a).or(b).and(c)) actually means if( (a || b) && c) because of how order of operations works. See Grouping below for more information.

Indeed

Begins a generic chain.

Chainable methods: and, andNot, or, orNot, butNot, and xor

Chain limit: none

if (indeed(a).and(b).butNot(c).or(d).test())Chaining is off by default with indeed, so that you can make simple comparisons:

// returns 'true'

indeed(a).is.true()

// returns 'indeed' so that you can assert more conditions

indeed.chain(a).is.true() // .and(b).is.false().test()When chaining, use .test() or .val() to terminate the chain and evaluate the total result of the expression. Non-chaining is optimized for comparisons, so indeed(a).is.defined() will return true or false whereas indeed(a) by itself, will not. To assert on the definedness of a single thing, 1) chain: if (indeed.chain(a).test()), 2) use defined(): if (indeed(a).is.defined()), 3) use regular booleans: if (a). Calling one of the chain methods without calling a comparison will automatically turn on chaining, so that you can say if (indeed(a).and(b).and(c).test()) rather than if (indeed.chain(a).and(b).and(c).test()).

indeed is also equipped with some negation tools: not and Not. not simply negates the first condition:

if (indeed.not(a).and(b).test())is equivalent to

if (!a && b)Not negates the result of the chain, so

if (indeed.Not(a).and(b).test())is equivalent to

if (!(a && b))These too can be chained:

if (indeed.not.chain(a).and(b).test())

if (indeed.Not.chain(a).or(b).test())Either

Begins a chain where one of two conditions (or both) should be true.

Chainable methods: or

Chain limit: 1

Optimized for: existence checks

if (either(a).or(b))

if (either.chain(a).is.null().or(b).is.defined().test())Neither

Begins a chain where both conditions should be false.

Chainable methods: nor

Chain limit: 1

Optimized for: existence checks

if (neither(a).nor(b))

if (neither.chain(a).equals('foo').nor(b).is.a('date').test())Both

Begins a chain where both conditions should be true.

Chainable methods: and

Chain limit: 1

Optimized for: existence checks

if (both(a).and(b))

if (both.chain(a).is.false().and(b).contains('bar').test())AllOf

Begins a chain where all conditions should be true. Incidentally, it only makes sense to use this with more than two conditions. With two conditions only, use both.

Chainable methods: and

Chain limit: none

Chaining is on by default and cannot be turned off since any number of and's can be used

if (allOf(a).and(b).and(c).test())AnyOf

Begins a chain where at least one condition should be true.

Chainable methods: and

Chain limit: none

Chaining is on by default and cannot be turned off since any number of and's can be used

if (anyOf(a).and(b).and(c).test())OneOf

Begins a chain where exactly one condition should be true.

Chainable methods: and

Chain limit: none

Chaining is on by default and cannot be turned off since any number of and's can be used

if (oneOf(a).and(b).and(c).test())NoneOf

Begins a chain where all of the conditions should be false. With only two conditions, use neither instead.

Chainable methods: and

Chain limit: none

Chaining is on by default and cannot be turned off since any number of and's can be used

if (noneOf(a).and(b).and(c).test())NOf

nOf is the only helper that deviates from the standard structure. It accepts a number, and then any number of conditions, of which exactly that number must be true.

Chainable methods: and

Chain limit: none

Chaining is on by default and cannot be turned off since any number of and's can be used

if (n(2).of(a).and(b).and(c).test())Expect

Expect is identical to indeed and has all it's additional properties. It adds only a couple things: a throws comparison function (detailed below) for asserting that a function throws an exception, a with function for passing args to a function that should throw, and assert, which is the same as test but sounds more test-ish.

Grouping

You can create groups of chains, which are also evaluated left to right, using the properties And, But, Or, and Xor. They do what you would expect:

if (indeed(a).or(b).And.indeed(c).test())

if (indeed(a).and(b).Or.indeed(c).test())

if (indeed(a).and(b).Xor.indeed(c).test())

if (indeed(a).and(b).But.not.also(c).test())The first example evaluates a || b first and then the result of that with && c. But is an alias to And because sometimes it feels more natural to say "but" than "and." indeed also has several aliases that can be used after joins depending on what you want to say next:

// just like indeed

if (indeed(a).or(b).And.also(c).test())

// also just like indeed

if (indeed(a).and(b).Or.else(c).test())

// just like indeed, but negated

if (indeed(a).and(b).But.not.also(c).test())

// just like indeed, but negates the entire next group

if (indeed(a).and(b).But.Not.also(c).or(d).test())Additionally, all of the entry points are chainable after a Grouping property:

if (indeed(a).or(b).But.neither(c).nor(d).test())Matching

Most of the examples so far have been simple checks for definedness (for simplicity), but indeed has a wide variety of comparison functions as well. All of the chain starters also have the chainable properties does, should, has, have, is, to, be, been, deep, deeply, not, Not, noCase, and caseless. In addition, indeed and expect have andDoes, andShould, andHas, andHave, andIs, andTo, and andBe which let you use multiple comparisons on the same object (chaining must be turned on). Most of these simply allow chaining with natural language. However, deep and deeply turn on deep object comparison when using equal (below), not and Not negate the comparison, caseless and noCase turn on case insensitivity (for equal, contains, key, keys, value, and values), and roughly makes order not matter when comparing arrays (if they have the same number of elements and all the same elements, they are considered equal).

Equals

Compares objects using _.isEqual when deep is applied and using === when it's not.

if (indeed(1).equals(1))

if (indeed({foo: { bar: 'baz'}}).deeply.equals({foo: { bar: 'baz'}})Aliases: equal, eql

Matches

Checks whether a string matches the given regular expression. If given a string, it will convert it to a RegExp object.

if (indeed('foobar').matches(/oba/)) // or .matches('oba')Aliases: match

A

For type comparisons. This is more strict that typeof however. It checks for constructor.name (allowing custom types) and, failing that, uses typeof. It is worth noting that both the type and comparison are lower cased, so 'string', 'String', 'strIng', etc. are all equivalent.

if (indeed('hello').is.a('string'))An

Just like isA but preferable (for me anyway) for types beginning with vowels.

if (indeed([1, 2, 3]).is.an('array'))Contains

Indicates if the string or array contains the given value.

if (indeed('foo bar').contains('foo'))

if (indeed([1,2,3]).contains(1))Aliases: contain, indexOf

Key

Indicates if the object (or array, though somewhat by accident) contains the given key.

if (indeed({foo: 'bar'}).has.key('foo'))Aliases: containsKey, containKey, property

Keys

Like .key but for multiple keys. Keys can be passed as an array or multiple strings.

if (indeed({foo: 'bar', baz: 'quux'}).has.keys('foo', 'baz')

if (indeed({foo: 'bar', baz: 'quux'}).has.keys(['foo', 'baz']))Aliases: containKeys, keys, properties

Value

Indicates if the object (or array) contains the given value.

if (indeed({foo: 'bar'}).has.value('bar'))Aliases: containsValue, containValue

Values

Like .value but for multiple values. Values can be passed as an array or multiple strings.

if (indeed({foo: 'bar', baz: 'quux'}).has.values('bar', 'quux'))

if (indeed({foo: 'bar', baz: 'quux'}).has.values(['bar', 'quux']))Aliases: containsValues, containValues

Defined

Returns true for everthing except undefined. A little cleaner looking than if (typeof thing !== 'undefined'), though that's exactly what it does under the hood.

if (indeed('string').is.defined())

if (indeed(undefined).is.not.defined())Null

Returns true for null and false for everything else.

if (indeed(null).is.null())

if (indeed('string').is.not.null())True

Not to be confused with truthiness, this checks for the literal value true.

if (indeed(true).is.true())False

Checks for the literal value false.

if (indeed(false).is.false())Truthy

Checks for truthiness.

if (indeed(1).is.truthy())Falsy

Checks for falsiness.

if (indeed(0).is.falsy())GreaterThan

Compares two numbers

if (indeed(1).is.greaterThan(0))Aliases: gt, above

LessThan

if (indeed(1).is.lessThan(2))Aliases: lt, below

GreaterThanOrEqualTo

if (indeed(1).is.greaterThanOrEqualTo(1))Aliases: gte

LessThanOrEqualTo

if (indeed(1).is.lessThanOrEqualTo(1))Aliases: lte

Mixin

Additionally, indeed has a mixin method for extending these comparison methods. It takes an object of function names with corresponding functions.

indeed.mixin({

can: function(condition) {

return function(val) {

return typeof val[condition] === 'function';

}

},

beginsWith: function(condition) {

return function(val) {

return val.charAt(0).toLowerCase() === condition.toLowerCase();

}

}

});The custom functions should be in this form, where condition is the thing to match against and val is the original object (which seems a little backwards, since val is "inside"). These methods, for example, would be called like this:

if (indeed({ foo: function() {} }).can('foo').test())

if (indeed('hello').beginsWith('h').test())Tap

Executes a provided function, passing it this.

if (indeed(a).and(b).tap(console.log).or(c))As an Assertion Library

I didn't write indeed to be an assertion library, but when I discovered that most assertion libraries don't return true/false values from their assertion methods, thereby making them unusable with mocha-given (which I use), I realized that indeed already had everything it needed (under the hood) to be that kind of assertion library. It just needed a few semantic changes to make it sound like an assertion library.

Expect

expect is an alias to indeed. It does all the same stuff but sounds more test-ish.

Given -> @thing = 'foo'

When -> @subject.doSomethingNeat(@thing)

Then -> expect(@thing).to.equal('foo bar')Assert

assert is an alias to val and test. Once again, it's only purpose is to convey testing semantics. This only needs to be called when chaining multiple conditions.

Then -> expect.chain('foo').to.be.a('string').and.to.match(/o$/).and(['bar']).to.contain('bar').assert()Throw

Returns true if the passed function throws an error. An optional string, regex, error, or function can be passed for more refined assertions:

expect(fn).to.throw();

expect(fn).to.throw('Inconceivable!');

expect(fn).to.throw(new Error('Mischief is afoot'));

expect(fn).to.throw(/timeout/);

expect(fn).to.throw(function(e) {

return e.message.indexOf('!') > -1;

});Aliases: throws

With

Assign parameters to pass to the invocation of a method to assert with throw:

expect(fn).with('foo', 'bar').to.throw('FOO BAR'); // Passes 'foo' and 'bar' to fn when it's calledSpies

expect also checks it's parameter to see if it's a sinon spy or stub, and if it is, it extends itself with the spy, letting you call sinon methods (which are sometimes awkward) in more natural English. For example:

var spy = sinon.spy()

// ... test things with the spy

expect(spy).to.have.been.called // Doesn't this feel more natural than 'spy.called'When to use indeed for asserting

Indeed will work well with mocha-given or jasmine-given, but it isn't a full assertion library to be used in every project since it doesn't throw AssertionErrors or accept or generate messages (at least for now - perhaps in the next version I will get more abmitious). But because Then -> true is a passing test in Given style testing, it works well in that limited capacity.