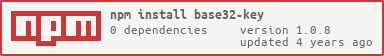

base32-key

v1.0.8

Published

A base 32 encoding for binary strings

Downloads

27

Maintainers

Readme

base32-key - A base 32 encoding for binary strings

Usage

Install

npm install base32-key

# or

yarn add base32-keyExample (es module)

import { fromHexString, toHexString } from 'base32-key';

console.log(fromHexString('c0ffee'));

// => '222ET-3ZZGN'

console.log(toHexString('222ET-3ZZGN'));

// => 'c0ffee'Example (commonjs)

var fromHexString = require('base32-key').fromHexString;

var toHexString = require('base32-key').toHexString;

console.log(fromHexString('c0ffee'));

// => '222ET-3ZZGN'

console.log(toHexString('222ET-3ZZGN'));

// => 'c0ffee'A base 32 encoding for binary strings

This document describes a human-readable base 32 encoding for binary strings. It is intended to be used for e.g. product keys, which may be printed on paper and entered using a keyboard. As such, it is important that codes are easy to read, easy to type, and that errors can be detected.

The encoding described here has some similarities with the Base32 encoding proposed by Douglas Crockford, which has similar goals, but differs in many of the details.

Overview of the encoding

The encoding algorithm works as follows.

- A binary string is split into 20 bit groups, left-padding with 0s if necessary.

- Each group is converted to four base 32 digits (using 5 bits per digit).

- For each group, we calculate a check digit using a 5-bit CRC.

- Each base 32 digit is encoded using the following 32 character alphabet:"23456789ABCDEFGHJKLMNPQRSTUVWXYZ". (Alternatively, the lowercase alphabet "abcdefghijkmnpqrstuvwxyz23456789" may be used.)

- Groups are joined with hyphens (-).

Calculation of check digits is described further below.

For example, 0x123456789abcdef (hexadecimal) contains 60 bits, so it is split into three groups (0x12345, 0x6789a, 0xbcdef). Each group is encoded separately. 0x12345 in hexadecimal is 00010 01000 11010 00101 in binary, or 2 8 26 5, with a check digit of 12. Using the uppercase alphabet, 2=4, 8=A, 26=U, 5=7, and 12=E, the first group becomes 4AU7E. The complete code is 4AU7E-EY6U6-RMHHH, where E, 6 and H are the check digits.

The decoding algorithm works in reverse. It should verify the check digit of each group, and inform the user which groups are invalid. The output of the decoding algorithm is the original binary string with padding.

Choosing an alphabet

Why base 32?

Bases which are powers of 2 are convenient to encode binary data, because they allow input data to be split into equally-sized groups of bits which can be encoded/decoded independently.

For textual representation of binary data, base 16 (or hexadecimal) and base 64 are the most common encodings. Base 16 has the benefit that each 8-bit byte corresponds with exactly two 4-bit hexadecimal digits, so the encoding preserves byte boundaries without the need for padding.

Overall, base 64 is more popular than base 16 because it is more compact: it can encode 3 bytes into 4 characters (33% overhead) instead of 1 into 2 (100% overhead). However, to achieve this, the base 64 alphabet must include both uppercase and lowercase letters and at least two non-alphanumeric characters.

This has two main disadvantages:

- Those last two characters are often problematic, which is why there are many different variants of base 64 that mostly differ in the chosen alphabet.

- Using both uppercase and lowercase letters makes it harder to spell out codes. Additionally, mixed case codes are more difficult to enter on mobile phones.

Base 32 is a compromise between base 16 and base 64. It allows encoding 2.5 bytes into 4 characters (60% overhead). If we add a check digit to every group of 4, as I propose, we are reduced to encoding 2.5 bytes into 5 characters (100% overhead) which is no more compact than base 16, but adds the ability to detect errors.

Most importantly, base 32 allows us to restrict our alphabet to digits and letters of one case only, which are easier for humans to write down and communicate verbally. These codes can safely be included in URLs and filenames without need for escaping and with little risk of corruption, mitigating many of the practical problems with base 64.

Eliminating ambiguous characters

The main problem with encoding binary data using ASCII characters is that, depending on the font, certain characters may be confused with others. For example, uppercase i (I) may look a lot like lowercase L (l), or the digit 0 may look like the uppercase letter O.

Other potentially confusing pairs are: 0/O/o, 1/I/l, 2/Z, 5/S, 8/B, U/V/Y, O/Q.

Since we only need 32 characters, we can start with all 36 letters and digits and eliminate some of the most confusing ones.

There are two ways to deal with groups of ambiguous characters:

- Exclude all characters in the group (e.g., neither '0' or 'O' is used).

- Collapse the ambiguous characters to a single representative element (e.g., '0', 'O', and 'o' are all interpreted as '0').

The first approach is the simplest.

The second approach allows us to keep one element of each ambiguous set, which as the benefit that we can eliminate more ambiguous groups overall. However, this comes with the disadvantage that readers that are unfamiliar with the details of the encoding might waste time scrutinizing a code, trying to distinguish '0' from 'O' for example, unaware that the distinction does not matter.

Crockford uses the second approach. However, considering the downside mentioned above, and since neither approach can eliminate all ambiguity, I favor the simpler first approach. I decided to eliminate the most confusing pairs: 0/O and 1/I.

Uppercase or lowercase?

We only need up to 26 letters in our encoding, so to avoid confusion, we will use only letters of the same case. But which one should we pick?

Uppercase letters have the advantage that they are printed larger and thus are more easily identified. Additionally, a string of uppercase letters is more easily recognized as a code rather than a word.

However, lowercase letters have the advantage that in most fonts, they are more easily distinguished from digits. For example, 5/s and 2/z are less ambiguous than 5/S and 2/Z in most fonts.

Finally, some ambiguities only exist in lowercase or uppercase. For example, 1 can be confused with lowercase l (but not uppercase L) or uppercase I (but not lowercase i). So the choice of letter case affects which pairs are ambiguous.

I've decided to favor uppercase characters, but provide an alternative lowercase alphabet too.

The base 32 alphabet

Two alphabets are provided:

- Uppercase alphabet:

23456789ABCDEFGHJKLMNPQRSTUVWXYZ(preferred). - Lowercase alphabet:

abcdefghijkmnpqrstuvwxyz23456789(alternative).

The uppercase alphabet consists of digits 2-9, followed by letters A-Z (omitting O and I).

The lowercase alphabet consists of letters a-z (omitting o and l), followed by digits 2-9.

Note that the alphabets differ in the letters I (included in lowercase form, but not uppercase) and L (included in uppercase form, but not lowercase).

Furthermore, letters were moved in front of digits in the alternative alphabet. This is intended to avoid confusion about which alphabet is used. Otherwise, most (but not all) letters would pair up, and entering a lowercase code in an input field that expects an uppercase code would work for some groups but not others, which would be very confusing. By making the ordering of characters very different such errors are more easily detected.

Check digits

Since codes are primarily intended to be read and written by humans, it is important to include check digits to verify that the entered code is correct.

Crockford proposes using the integer value modulo 37 as a checksum, which requires adding 5 more characters to the alphabet for the final digit. This has many of the same disadvantages as base 64 encoding. Since the extra characters aren't part of the usual alphabet, users might not even recognize them as being part of the code.

Instead, I propose a 5-bit cyclic redundancy check, so that the check digit is another base 32 digit, which is appended to the data digits and encoded with the same alphabet.

The CRC is based on the polynomial x^5 + x^2 + 1 (also known as CRC-5-USB). This particular polynomial was chosen because, when used in a 5 character group, it detects:

- any individual character replacement (e.g. ABCDE -> XBCDE).

- any transposition of adjacent characters (e.g. ABCDE -> BACDE).

- any substitution of one character with another (e.g. 22ABC -> ZZABC).

The first two kinds of errors are common when entering codes using a keyboard, while the third kind occurs when one character is mistaken for another (like 2 for Z, one of the ambiguous pairs that we didn't eliminate from the alphabet).

For reference, the Python code below calculates the CRC-5 of base 32 numbers:

CRC5_TAB = (

0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 17, 30, 27, 13, 8, 7, 2, 25, 28, 19, 22,

26, 31, 16, 21, 14, 11, 4, 1, 23, 18, 29, 24, 3, 6, 9, 12)

def CalculateCrc5(digits):

crc = 0

for digit in digits:

crc = CRC5_TAB[digit ^ crc]

return crc

assert CalculateCrc5([2, 8, 26, 5]) == 12

assert CalculateCrc5([28, 29, 30, 31, 0, 1, 2, 3]) == 20Grouping of digits

In principle, we could encode an arbitrary byte string and add a single check digit at the end. This would give us a 96.875% probability of detecting errors. This is similar to what Crockford proposes. However, this has the downside that we can only verify the validity of the code after it is entered in its entirety, and we cannot tell the user where the error occurred. For longer codes, this would be very frustrating.

Moreover, long strings are hard to read for humans, which is why some kind of grouping is desirable. My proposal is to group the data into 20-bit words, encoding each word independently into five characters including one check digit. Groups are separated by hyphens.

This format has several advantages:

- Separating long codes into groups of characters greatly increases legibility.

- Including a check character in each group reduces the likelihood that errors go undetected in long strings, because it is impossible for errors in separate groups to cancel each other out.

- It becomes possible to tell the user which group exactly contains an error, instead of rejecting the whole code. This is much more user-friendly.

- Each group can be validated as it is entered, making it easier for users to correct mistakes.

It would be preferable to choose a group size that aligns to a byte boundary, but unfortunately, the least common multiple of 5 and 8 is 40, so the smallest group size would use 8 digits (excluding the check digits) to encode 5 bytes. These groups would be too long for humans to process one-at-a-time.

Grouping by five digits (4 data digits + 1 check digit) is a reasonable alternative: the groups are small enough to be easy to read as a whole, while every 2 groups encode 5 whole bytes.

Separating character

I selected the hyphen ('-', technically, the ASCII minus sign) as the separating character, because:

- It is safe to use without escaping in URLs and filenames.

- Text viewers (email clients, web browsers, and so on) may naturally break long codes after a hyphen, which improves formatting. Unlike other punctuation marks, a hyphen at the end of the line suggests that the code continues at the next line.

An input dialog that is designed to accept base 32 codes could group digits automatically without requiring that hyphens are entered explicitly. This is particularly helpful on mobile devices.

Test vectors

Below are some examples of inputs and the corresponding encodings. Feel free to use these for testing purposes.

Hexadecimal input: fedcba9876543210 (64 bits)

Uppercase grouped: 222HQ-XR7UV-M3V7M-AEJJS

Lowercase grouped: aaary-7zf45-vb5fv-inss2

Uppercase ungrouped: HXR7UM3V7AEJJW

Lowercase ungrouped: r7zf4vb5finss6

Hexadecimal input: f8956c40a3a2d978dbc3 (80 bits)

Uppercase grouped: Z4CQN-SJ759-NDERZ-KQY5V

Lowercase grouped: 9ckyw-2sfdh-wmnz9-ty8d5

Uppercase ungrouped: Z4CQSJ75NDERKQY54

Lowercase ungrouped: 9cky2sfdwmnzty8dc

Hexadecimal input: cbd3e8a1494 (44 bits)

Uppercase grouped: 222ET-RNZAY-N76N9

Lowercase grouped: aaan3-zw9i8-wfewh

Uppercase ungrouped: ERNZAN76NM

Lowercase ungrouped: nzw9iwfewv

Hexadecimal input: 867ffd93c9dff77a08f2ea98b10682cb53d590cf64ae55a823 (200

bits)

Uppercase grouped:

JTZZK-V6YBQ-VZVR3-N49LS-XCED2-43N4Y-TFBXT-D68HR-ELR7M-DC35X

Lowercase grouped:

s399t-5e8jy-595zb-wchu2-7knma-cbwc8-3pj73-megrz-nuzfv-mkbd7

Uppercase ungrouped: JTZZV6YBVZVRN49LXCED43N4TFBXD68HELR7DC35M

Lowercase ungrouped: s3995e8j595zwchu7knmcbwc3pj7megrnuzfmkbdv

Ideas not pursued

Wider checksums

From an information theoretic point of view, having a check digit per group is not optimal: for long strings, the probability that an error is detected is maximized if all check digits are affected by all input bits. For example, if we have a 100-bit input, it would be better to append a single 25-bit CRC over the entire input than have a 5-bit CRC for each 20-bit group. However, this has the disadvantage that we can only reject the input in its entirety, without pointing out the user's error.

Chained/inverted CRCs

It's also possible to chain the check digits between groups (so that the second group's check digit checks all preceding 8 data digits, instead of only the preceding 4). This would allow us to detect errors when one or more groups are dropped from the front of the code. However, this is unlikely to be a problem in practice (if codes are truncated, groups are more likely dropped from the end) and increases implementation complexity.

When calculating CRCs, it is common to invert the bits of the CRC before (and sometimes also after) calculation. This is done to detect differences in the number of leading zeroes in the input, which would otherwise generate the same check digit. However, when using fixed-size groups, this is not necessary.

Eliminating offensive words

Using letters in the encoding alphabet has the risk that some combinations of letters might form offensive words. Crockford eliminates the letter U from his alphabet for this reason.

However, this is far from a satisfactory solution. Even in English, there are many offensive words using the remaining letters. Even if we went so far as to remove all vowels, offensive abbreviations (like "KKK") or misspellings ("FVCK") would remain. And that's not even considering other languages than English, which may have their own taboo words.

On the other hand, offensiveness might not be much of a problem in practice. People can easily recognize that codes are not regular English text, and although they might notice an offensive substring if it appears by random chance, they will probably realize this is purely a coincidence, and are unlikely to feel seriously offended.

So since guaranteed inoffensiveness is impossible, and potential offensiveness is not likely to be a problem, it's best to ignore the problem entirely instead of inventing convoluted solutions.

If this is not acceptable in a particular context, it may be possible to filter out offensive codes after the fact. For example, if a company generates random product keys, they can check the generated codes against a blacklist and discard keys that are deemed offensive. This approach requires that the input bytes can be changed to suit the extra requirements on the encoded output; this might not always be possible, for example, when encoding cryptographic hash codes.

Padding of input / detecting truncated output

Encodings like base 64 typically use padding characters to specify how many input bytes are encoded in the final block. This is necessary because base-64 (like base 32, but unlike base 16) does not naturally align to byte boundaries.

There are many ways to address this problem, with different advantages and disadvantages:

- Should only the number of bytes in the final block be encoded, or the total number of bytes? (The latter has the advantage that truncated codes can be detected.)

- Should the number of bytes or the number of bits be encoded? (The latter has the advantage that bit strings can be encoded.)

- Should padding use different characters from the regular alphabet (as with base 64) or not?

- Should the last block be allowed to use fewer than 5 characters instead?

In the end I decided to not define any padding, because different schemes are suitable for different use cases. For example, if we use the base 32 encoding to generate 120 bit product keys, the output always consists of 6 groups, and no padding is needed. Similarly, if leading zeros do not change the interpretation of the input (for example, when encoding large integers) encoding the number of padding bytes is unnecessary.

For use cases where the input length does matter, it is easy to perpend a fixed-size prefix that specifies the length of the original input. This would also allow truncated codes to be detected.